By Benji

Benji is a member of the Kurdistan Solidarity Network and an occasional attender at hislocal Quaker Meeting with a long-standing interest in both the Quakers and other home-grown radical movements.

The Kurdish freedom movement often talks about the ‘two rivers’ of history: the river of Capitalist Modernity and the river of Democratic Modernity. The former refers to the history of state hegemony, capitalist realism and Darwinian competition that forms the only history most are ever exposed to, whilst the latter refers to the far older history of democratic society, communalism and mutual aid that predates it and has presented a continual resistance. The Kurdish movement identifies with this second current, but only as one example out of many.As part of the movement’s call to build ‘world democratic confederalism’, it encourages everyone to learn the oft-suppressed democratic history of their own geographies. If we are to work towards democratic modernity within our own environs, we must be aware of this local history and build relationships with the democratic forces already hard at work all around us. This requires an ability to recognise such forces, beyond simply the words they use to describe themselves: every nation-state from the UK to the North Korea claims to be a democracy, and yet clearly, they will be no allies in our struggle. How, then, can we recognise these truly democratic forces? How can we identify those who are making their own ‘cracks in the wall’ (ii)?

A structural analysis can be helpful here. We can assume that a democratic organisation will empower its democratically minded members to thrive within it, whilst also safeguarding against co-option by those less co-operatively inclined; therefore, we can expect there to be many similarities between the structures that work for such movements and those that don’t. However, even the points of difference may be informative, and help us to translate the ideas of the Kurdish movement into our own context.

In this article, then, I’d like to talk about one such organisation with a powerful presence in the democratic history of the UK (and beyond), and one whose structures have proved themselves resilient over several hundreds of years: the Religious Society of Friends, more commonly known as the Quakers.

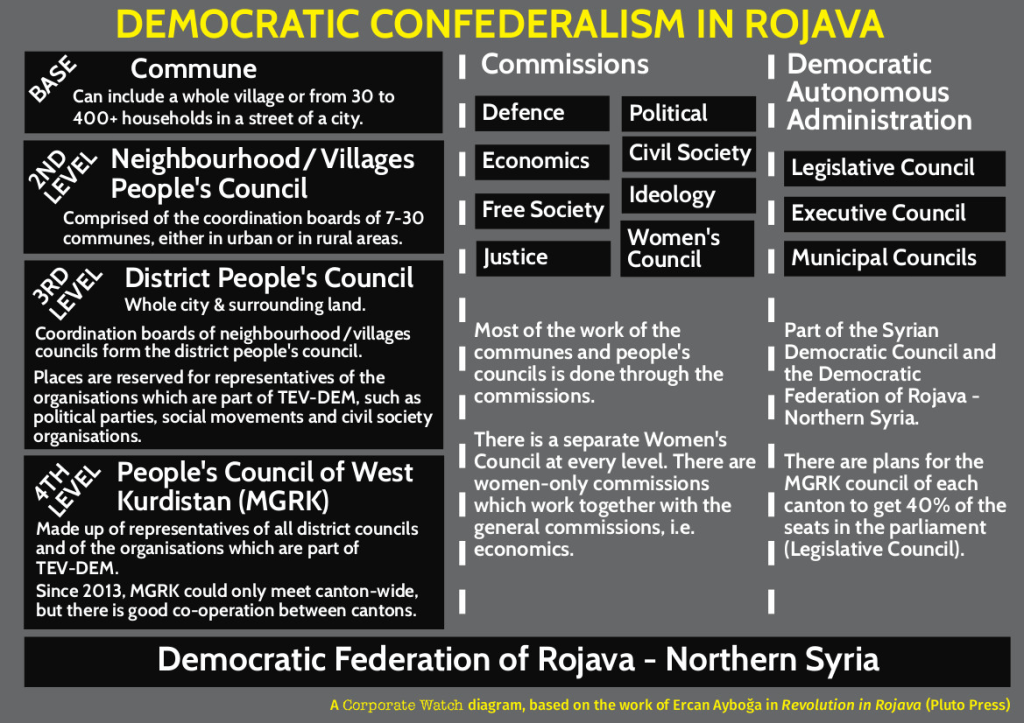

I see many parallels between the Quaker system of meetings and committees and the Kurdish model of democratic confederalism, both of which aim to guarantee subsidiarity by focussing on local groups (whether ‘meetings’ or ‘communes’) as the core organisational unit, whilst also structurally dissuading individualism in favour of collective action through cleverly-designed structures and mechanisms of accountability. Similarly, both rely on the establishment of adjacent structures (some short-lived, some longer lasting) to focus attention on particular areas or issues, or to provide a space for members united by a common characteristic (such as youth).

The two also appear to be in sync when it comes to perhaps the two most important aspects of any organisation: how it makes decisions, and how it deals with internal conflict. In the former, Quakers are distinguished by the process of ‘Quaker decision-making’, in which a designated clerk is responsible for discerning, in the form of a minute, the ‘sense of the meeting’ once all present have had an opportunity to reflect and comment on the question at hand. This minute is then returned to the meeting to review, amend (if felt necessary) and eventually adopt, though it is crucial to note that this does not require unanimous support—only that everyone present agrees that it accurately reflects the ‘sense of the meeting’. Similarly, Kurdish organisations aim to build consensus and have implemented various mechanisms to ensure that minority views are not lost amidst majority preference, such as quota systems.

Internal conflict, meanwhile, is dealt with in Quakerism through (you guessed it) more meetings. This is only one option, however, and the Quakers are happy to highlight that ‘Friends were among the pioneers of conflict resolution as a distinct activity’ (iii). Whether through mediation, counselling or ‘a quiet but firm reproof’, Quakerism has a rich tool box of ways to defuse internal conflict and correct harmful behaviours, all taking place in the same spirit of mutual trust and a supportive community as tekmîl sessions within the Kurdish Freedom Movement.(iv)

However, none of this is to say that both movements are identical (nor would we expect them to be). They have both emerged from very different political situations, social milieus, and cultural contexts and this necessarily has a deep impact on the resulting forms of each movement. However, I want to argue that what may at first appear to be irreconcilable differences may not be quite the obstacles they seem.

The first obstacle may well be what the Quakers are best known for: pacifism. How could the world’s oldest peace church possibly have anything in common with a movement that originated in a campaign of armed struggle against the Turkish state, and which continues that struggle in the various regions of Kurdistan today? I think that this comes from a misunderstanding of the Quaker peace testimony. In line with the Quaker position on all issues, exactly what this testimony entails is left to the discernment of each individual Quaker. This was seen in both the First and Second World Wars, where Quaker responses ranged from reluctantly joining the Armed Forces, to volunteering to serve in non-combatant roles, to strict conscientious objection (usually resulting in prison sentences, or worse). Reinforcing this diversity of opinion, a section in Quaker Faith & Practice dedicated to highlighting the ‘dilemmas of the pacifist stand’ includes a 1661 quotation which could well be seen to echo Öcalan’s ‘rose theory’ (v) of ‘legitimate self-defence’ when it states that ‘a great blessing will attend the sword where it is borne uprightly to that end and its use will be honourable’ (vi). In short, there are many different interpretations of just what this testimony requires from Quakers, and whilst many (perhaps even most) may take it to mean some form of pacifism, it is not necessarily as settled an issue as it may appear at first.

Another clear difference may be the role of women in both movements. Whilst both movements are distinguished by the number of women in positions of great influence throughout their histories—Margaret Fell could well be seen as a proto-Sakine Cansız for her role in documenting the activities of the early Quaker movement—the current state of affairs is very different. The Kurdish movement, through its separate women’s structures, quota system and male and female co-chairs, takes a more essentialist, separatist approach, whereas there is no contemporary parallel in Quakerism. However, it is worth noting that that has not always been the case; there were separate Women’s Meetings, both Yearly and local, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, ending with the merging of the two Yearly Meetings in 1908 (though whilst they limited membership to women only, these did not have the same autonomy from the male-dominated general meetings as the Kurdish women’s structures today).

The third, and perhaps most obvious, difference is that one movement faces existential threats on a daily basis, and the other does not. The Quakers do not maintain any independent territory; the Kurdish movement controls the liberated areas of north-east Syria. Quakers have never faced ethnic cleansing or genocide at the hands of either NATO militaries or Islamist terror cells; both are a daily reality for the Kurdish movement. The Quakers maintain an office at the UN; much of the Kurdish movement is internationally criminalised, and Öcalan remains imprisoned.

Obviously, these two movements operate in wildly different contexts, but I would suggest that this represents a good reason for us in the UK to study such local examples. The tactics, innovations and ideas that work for the Kurdish movement are unlikely to be exactly the same ones that work for our movements, and attempting to port them over directly is a recipe for disaster. But what could be more applicable to the British context than a movement still coming to grips with its complicated history of opposition to, and complicity in, the trans-Atlantic slave trade; a movement that can move successfully within liberal democratic spaces, even whilst stressing the supremacy of one’s conscience over the laws of states: a movement that inculcates in its members effective techniques of mental self-defence against capitalist modernity (though without using either of those terms); and, last but by no means least, a movement that operates in English, rather than Kurdish?

This is a shortened version of an article published on 8 December 2022 at:https://kurdistansolidarity.net/2022/12/08/of-kurds-and-quakers/

ii) https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2015/05/10/the-crack-in-the-wall-first-note-on-zapatista-method/

iii) https://qfp.quaker.org.uk/passage/4-23/

iv) https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/philip-arge-o-keeffe-tekmil

v) https://medyanews.net/abdullah-ocalan-on-self-defence-honour-and-love-rose-theory/