By Nora Ziegler

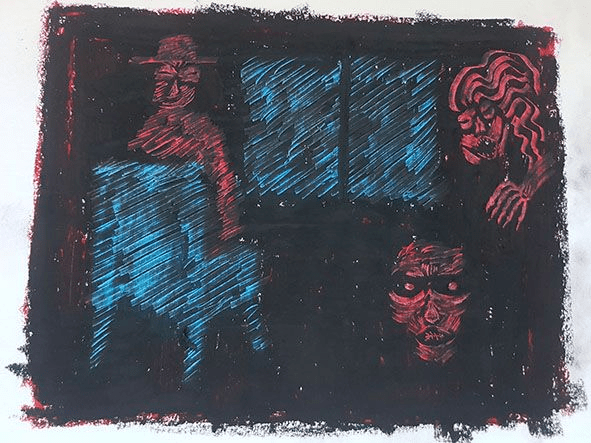

In moments between sleeping and waking I see things. Ghosts live in those spaces between reality and imagination, between the dead and the living. And sometimes in those spaces I violently shift perspective. I become the ghost. I become a man who hurt me, tasting his knowledge and indifference. I become the Erinyes, I become a poltergeist, I am rage. I float through walls and listen to the steady breathing and familiar snores of my house mates. I become the one who haunts and is haunted, who protects and seeks protection.

I dreamed of an angel. She told me of a magical place where I could be with my loved ones. She guided me through the woods, squeezing between bushes and brambles until we emerged in a clearing where the air was sweet and dense. My feet release the ground, I dance, surrounded by the spirits that love me and have never left my side. I float and frolic, I cry and laugh out loud. Then I feel a cold hand on my shoulder and a voice whispers in my ear: ‘someone else is here too’. Terror. The hand pulls me backwards, out of my dream into my bed. I can’t move. I still feel the hand pressing on my shoulder, and I feel the evil presence in my room. It’s back. I should have known that if I reach out to those who love me, it too can find me.

I am always careful not to address the evil presence directly. I fear making contact, inviting it into a conversation I can’t possibly hold. Scared of losing control. I don’t think this is lack of faith. I have agency and responsibility, I have the power to engage with evil, and God can’t always protect me from myself. Even by writing about this now I fear I might invite it back.

It first started while I was living at the London Catholic Worker. I was part of a small group of activists running a house of hospitality for homeless migrants and refugees. Our house of hospitality was teeming with desire, care, hurt, guilt, hope, resentment, anger, depression. So many different lives and trajectories intersecting. And we were living acutely, in our everyday interactions, the violent contradictions of the border, of racial capitalism, patriarchy, and the non-profit industrial complex.

In Ghostly Matters, Avery Gordon writes: ‘the ghost cannot be simply tracked back to an individual loss or trauma. The ghost has its own desires, so to speak, which figure the whole complicated sociality of a determining formation that seems inoperative (slavery) or invisible (like racially gendered capitalism) but that is nonetheless alive and enforced’[i]. Ghosts are traces of power relations that we struggle to grasp in any other way. By turning away from the ghost, we turn a blind eye to its suffering and to its unfulfilled promise. We give up our power to perceive, and maybe even to act, and the possibility of breaking familiar and oppressive patterns. Avery asks, ‘if we shift perspective, begin to approach the ghost’s desires, what will we find?’ What might we learn about ourselves and our relationships? What possibilities for action and change might we discover?

Night after night the evil presence besieged me. It was a darkness within me but also outside, palpable, overwhelming, shared.

At the time I was seeing a Catholic spiritual adviser. This was a kind of pay-as-you-can therapy where I could talk about spiritual experiences too. My adviser introduced me to the Rules for the Discernment of Spirits by St. Ignatius of Loyola. Among other things I learned that ‘the enemy acts like a woman, in being weak against vigour’. But aside from the misogyny it was good to be taken seriously and to talk about how I might defend myself against my tormentor.

Not every guest is welcome. There are dangers, abysses. How do we open doors to the spiritual world without losing our footing in ‘objective’ reality? At the Catholic Worker too much responsibility was concentrated on a small group of core volunteers. I was under so much pressure I lost my sense of right and wrong, up and down, my capacity to reason and to discern. What I have learned from this is that discerning the spirits is a shared practice. We can’t do it alone. Discerning the spirits requires collective experience and confidence built over time from the ground up. Learning from mistakes, learning from each other, holding each other.

In Borderlands/La Frontera, Gloria Anzaldúa writes, ‘we’re not supposed to remember such otherworldly events. We’re supposed to ignore, forget, kill those fleeting images of the soul’s presence and of the spirit’s presence. We’ve been taught that the spirit is outside our bodies or above our heads somewhere up in the sky with God.’[ii] She writes that Western culture has split reality into two: an ‘objective’ reality, and the world of the soul and the spirit which she insists is just as real. She identifies this dichotomy as the root of all violence.

We can’t heal this dichotomy by simply declaring that the ‘objective’ and the spiritual are one and always have been. It is hard and thankless work mending these rifts created and reinforced by histories of violence. This work is done by people and communities who are ‘forced to live in the interface between the two’. And I think activist, mutual aid, anarchist and other collective organising spaces are such communities. You are forced by your struggles against oppression, your struggles for authenticity and justice and the struggles you have joined in solidarity. And so sometimes our work of resistance and building alternatives involves talking about ghosts, learning to live with them and collectively approaching them. What will we find?

[i] Avery Gordon, 2008, ‘Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination’. Pages 175 and 183

[ii] Gloria Anzaldúa, 1987, ‘Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza’. Pages 36 and 37