Between Ghazal and Reham

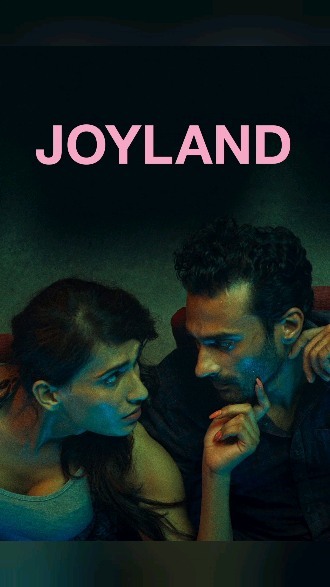

Joyland is a ground-breaking Pakistani film that pushes the boundaries of Pakistani cinema. It tells the tale of an unhappily married Haider who falls for a transgender woman called Biba. The film was initially banned in Pakistan but was then approved for release after some edits.The central theme of the film is desire. The desire that Haider feels for Biba. That Mumtaz feels for her husband Haider and the longing for freedom. The suppressed desire that his father Rana feels for his neighbour Fayyaz. Due to the constraints in Pakistani society with rigid patriarchal societal roles and cultural taboos, the characters exercise different levels of courage in acting upon their desire. Powerfully, it is the women who have the courage to be vocal about their needs.

The film is billed as a love story, but you don’t quite believe in Haider and Biba’s love in terms of how fleeting the relationship is. Perhaps they’re trying to show the impossibility of loving a transgender woman in a society that discriminates against the hijra class. Rather than Haider falling in love, you feel that Haider’s romantic liaison with Biba allows him to play out his gay sexuality. In Biba, you get a sense of a character who doesn’t allow herself to fall in love and holds back.

Another perspective is that Biba doesn’t hold back, although she’s quite cautious, as she has to be to survive. She does make herself vulnerable for Haider and she does sincerely fall in love with him. However, Haider doesn’t feel the same. He was in love with what she could provide him by allowing him to enact his repressed homosexuality. It seemed like he found a loophole with Biba. She’s presenting as a woman which imitates heteronormative relationships, but because Biba is trans, he can fulfil his desire. You can tell he doesn’t see Biba for who she is.He protests her getting surgeries to support her transition, and during an intimate scene he puts himself in a position that makes her realise that he doesn’t see her as a woman.

The main story of Haider and Bibi is not quite as compelling as that of his wife Mumtaz. She’s always supportive of her husband, but there is this strength and masculinity in her. But because of the gender roles, she cannot really express her authentic self. In one scene, Haider is finding it difficult to kill a goat as directed by his father, but Mumtaz offers to do it for him. But she isn’t permitted to perform this role for him, which could potentially emasculate him. Mumtaz is also supportive of Haider as a wife, but he is quite a weak character. He isn’t a good friend to her. He doesn’t have her back. Not in terms of masculinity, but he doesn’t really support her. She sacrifices a lot for him, and he can’t do the same for her. In a way he is pressured by his family.

Further breaking down the goat chasing scene, you start to see the dynamics within the family and Haider’s role. The father, Rana, is the patriarch and he upholds and imposes traditional gender roles in his family. By pressuring Haider to slaughter the goat he is forcing him to be brutal, to be masculine. When Haider is exhausted from chasing the goat he orders Mumtaz to fetch Haider water rather than Haider fetching it for himself. Mumtaz helps pin the goat down with Haider, symbolic of how she supports him, Haider is then yelled at by his father to kill the goat quickly, Haider hesitates for too long and Mumtaz takes it upon herself to commit the slaughtering. This action of Mumtaz tells us she can be brutal, be masculine, that it is easier for her to taken on that role compared to Haider. Mumtaz goes out of her way to be there for Haider, by providing financial support for his family and emotional support for him. She’s happy to do this because she likes her job, and she gets to work. On the note of Haider not supporting Mumtaz, it’s painful to see how we find that out. Haider is pressured to find a job and once he does, his family decides that Mumtaz should now stop working to help with the housework. This happens over dinner, and Mumtaz’s needs and objections against this decision are ignored, she looks at Haider for support and he cowers away and remains silent. He feels powerless and her power is taken away from her leaving Mumtaz heartbroken.

The sub lot of Haider’s father Rana getting into a romantic tryst with his neighbour Fayyaz is also quite poignant. Fayyaz makes a routine neighbourly visit but ends up staying the night at the house due to the father having some difficulties and then to keep him company. Despite their adult children chiding the potentially blossoming couple, the neighbour is daring enough to say she does not care what others think. That Fayyaz is in her autumnal years and owns her longing for companionship is an equally daring part of the film in a society that barely acknowledges older women’s sexuality. The father does not have the same courage as her and you feel a sense of sadness of what could be for these two older lonely souls.

His lack of courage also shows you that men themselves are entrapped in these toxic and rigid patriarchal rules, he longs for companionship too, but because he finds power in these rules, to go against them could jeopardise his power, his world, his position in society.

It was brilliantly refreshing to watch this film from Pakistan that explores human desire.

Agreed.

You can watch Joyland with a subscription (or a 14-day free trial) at the BFI, or at a certain union-busting, market-monopolising, surveillance-supplying multinational.

Ghazal Tipu is a communications professional and writer and recently completed an MSc in Psychology.

Reham Bastawi is a migrant solidarity activist, and writer, who comes from a North Sudanese Muslim background, and grew up in Brighton and Khartoum. Currently based in Pembrokeshire, Wales.