By Nora Ziegler

The dominant culture tells us that we must either be isolated or suppress our differences for the sake of connection. Offering and receiving hospitality can enable us to work across differences, recognising the risks of exploitation and abuse, as well as the opportunities for solidarity and transformation.

I live communally with 5 other people. We eat together, we support each other with our different needs and struggles, we meet together every week to discuss all kinds of issues that arise when people live together. Every morning, some of us also gather for prayer which involves a call and response liturgy, bible readings, and some time for silent reflection, during which individuals sometimes pray out loud for each other, for people we know, and for our wider society and world.

I feel blessed to have this shared space in which to practice my faith with my house mates. For me, the repetitive prayers are a discipline that teaches me to focus and be present in the moment. Praying together also helps me to build trust and softens my heart towards the others, which helps me navigate the frustrations and tensions of communal life.

Currently, my housemates and I are all Christian, but this has not and will not always be the case. I have been thinking about what we might do when someone with a different faith joins our community. Would we pray separately? Would we try to find some middle-ground so everyone can participate equally? Or could we find a way of inviting each other into our different prayer lives? Perhaps we could take turns in hosting prayers or participating as a guest.

Inviting people with different or no faith backgrounds to participate in my spiritual practice is a big responsibility. I would try to avoid language that might alienate or offend my guests, but I would also want to give them a genuine sense of what my faith is about, and what is meaningful to me. I won’t always get that balance exactly right, but I learn by trying things out and asking for feedback. Hospitality is often awkward! There is so much room for misunderstandings and mistakes, but also for intimacy and growth.

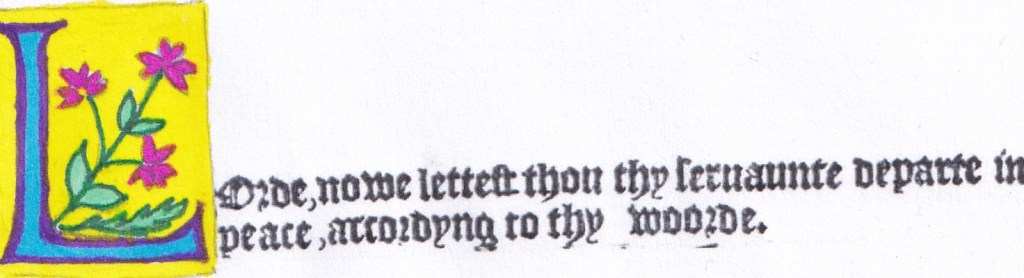

There is a Christian prayer called the “Nunc Dimittis” which begins with the words “Lord, now you are letting your servant depart in peace”. This prayer is meaningful to me because I used to pray it late at night before going to sleep, during a time where I was overworked and stressed doing what I felt called by God to do. I would feel embarrassed saying this prayer out loud in front of non-Christian friends, especially anarchists, because of the strange language referring to a Lord and servant.

But it could potentially also open up interesting conversations. Hospitality can be an opportunity to get to know another person through their language, their symbols and worldview, not our own.

Mohamed Abdou has written about ethics of hospitality, or Uṣūl al-Dhiyafa, as the foundation for working across difference. Hospitality in any context means that there is a difference between the host, who welcomes, and the guest, who enters an unfamiliar space. Instead of assuming that we must come together on equal terms, hospitality recognises differences and enables different groups and movements to invite each other into their spaces and approach each other with humility and curiosity.

Practicing hospitality in this way encourages us to develop a sense of who we are, why particular issues matter to us, and why we adopt certain practices and tactics. Instead of assuming that our concerns, cultural codes and tactics are somehow universal. This self-awareness enables us to build alliances with other groups and movements fighting the same oppressive systems, but who might not share our priorities and tactics. Shedding the weight of universality also frees us to look at some of our own practices more critically!

Offering hospitality enables oppressed groups to build autonomous spaces without having to isolate themselves from other groups and movements. Autonomy does not mean separation; in fact, it enables connections because autonomous spaces provide a level of safety where we can develop and gain confidence in our leadership skills and gently rebuild our capacity to engage with conflict and difference. Autonomy therefore empowers us to be generous hosts to our allies.

For socially dominant, such as white or middle-class groups, offering hospitality could mean making an effort to welcome working-class, disabled, Global Majority and other marginalised activists into their spaces, and engage with the different perspectives and skills that they bring. Instead of expecting them to make all the effort to adapt and learn the dominant codes and practices in order to participate “equally”. This shouldn’t mean treating people as perpetual guests but doing the work that will enable people to participate in their own ways, on their own terms.

Hospitality enables relationships to change. People go from being strangers or outsiders to feeling at home, and people who are used to being in charge, learn to be at home in spaces where they are not in control. Hospitality therefore allows power dynamics to shift and destabilise in ways that create new challenges, new responsibilities, and new possibilities for growth.

Finally, hospitality enables us to learn and share cultural, political and spiritual practices that ground radical grassroots organising and action. For example, the Kurdish Freedom Movement invites activists and revolutionaries from other countries and movements to participate in and learn about their political and cultural practices, such as revolutionary friendship (Hevaltî) or the chanting of “Jin Jiyan Azadî” (women, life, freedom). International allies adopting and celebrating Kurdish practices can also help resist the appropriation of Kurdish culture by Nation States such as Turkey and Iran.

In the dominant system, the more social and economic power people have, the more our spiritual and cultural lives are impoverished. Accepting invitations to learn and be inspired by other communities and movements can enable us to rebuild a radical culture from the grassroots while offering resources and social power as part of ongoing relationships of solidarity.

Nora Ziegler is a writer and community

organiser. She is currently training as a local

preacher in the Methodist Church.